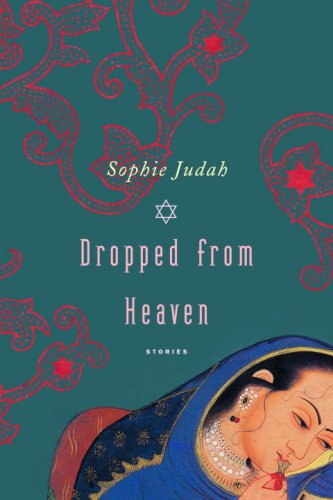

Items related to Dropped from Heaven: Stories

In the mythical village of Jwalanagar, the Jewish traditions of the Bene Israel have survived for more than two thousand years, but the twentieth century brings with it modernity and cataclysmic political change. In these nineteen interconnected stories–by turns insightful, humorous, and heartbreaking; poignant, gentle, and searingly sad–we follow this community across the years as its way of life is forever altered.

In “Hannah and Benjamin,” the parents of a young woman are shocked when she defies their rejection of the man she wishes to marry–but no more shocked than the man himself. In “Nathoo,” a kindly Jewish soldier and his wife adopt a Hindu boy orphaned in the post-independence violence of 1947–with disastrous results. In “Dropped from Heaven,” a mother with three unmarried daughters at home and a copy of Pride and Prejudice in her handbag springs into action when she hears that two single brothers are coming to town looking for brides. And in “Old Man Moses,” a lonely and imperious old man is visited by his Israeli grandson and the young man’s girlfriend, and finds that there is still a place in his heart for love.

Sophie Judah tells these stories in a wonderfully fresh and original voice, and gives us a fascinating look at an ancient, vibrant community that now exists only in memory.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

I first met Joseph on a hospital ship returning from South Africa. We had both been wounded during the early days of the Boer War and were being shipped back home to India. I had passed a restless night. The wound in my shoulder was healing, but pain made sleep difficult. I spent my time looking out of the porthole, and I watched the horizon change colors from black to gray, to streaks of pink, orange, and purple. After the sky turned a pale blue, I heard one of the other patients stir in his bed. This gave me something different to watch. I saw the dark shape of a man rise from his bed, fumble for something in his locker, and then limp toward the door. He had a crutch under one arm and a parcel under the other. He had trouble opening and closing the door, but I did not get up to help. The bloke obviously thought that he could manage by himself, so I was not going to be the one to remind him that he was incapacitated at least for the time being.

The man stood in the open doorway for a few seconds. The bundle under his arm caught my attention. He did not raise his arm or remove the parcel he held against his body, although it would have made it much easier for him to open the door if his arm could move unhindered. He placed his crutch against the bulkhead outside the door, hopped through on one leg, and then reached back to pull the door shut. I heard the sounds of the crutch on the stairs followed by creaks when each stair took his weight as he hobbled along. I wondered what made the bundle so precious that he would not let it drop. Letters from a wife or sweetheart did not normally get the amount of respect this fellow was showing for his parcel. It was also too large to contain letters, anyway.

We had been in South Africa for only a few weeks. I tried to think of other things, but my mind kept returning to the bundle under the wounded soldier’s arm. Its shape was vaguely and disturbingly familiar. I did not understand the uneasy feeling of guilt that overcame me. I had not hurt the man’s pride by helping him, so I had no reason to feel that at that moment I should have been doing something other than lying in bed imagining the naked bodies of the nurses who took care of us.

Eventually my curiosity got the better of me. I rose and went out on deck. Not far from the door I saw the answer to my riddle. The man stood with his back not completely to the rising sun but at a slight angle to it, so as to face northwest. He was covered with a tallit, or prayer shawl. His held his crutch under one arm for support, while in his free hand he held a small book. The empty bags that had held his prayer shawl and phylacteries, or tefillin, lay on a chair beside him. I did not have to look at the man’s face to realize that he was one of my people. As “natives” we could not become officers in the British Army. This man had come from my ward, so he was an enlisted man, not an officer. Officers inhabited a different part of the ship. I understood the reason for my unease. I should have been praying, too. I always carried my tallit into battle with me so that in case I got killed my body could be wrapped in it for burial. I did not carry tefillin because I did not pray regularly. Still, I wanted a Jewish funeral if it was possible.

I waited for the man to finish his prayers and place his “holy things,” as I thought them to be, into their bags before I stepped forward and introduced myself.

“Shalom aleichem,” I said, as it was the only Hebrew greeting I knew. “My name is Bentzion.”

He took my hand in a firm clasp. “Joseph,” he said.

“Could we speak for a while? Would you like to sit here or shall we go below?” I asked.

“I’d rather sit out here, but my wound hurts in the cold.”

“Shall I bring up two blankets? My wound hurts, too.”

“That would be nice,” he replied.

This was the beginning of a friendship that lasted all our lives. I accompanied him to the deck every morning and evening during the rest of the voyage home. He allowed me to carry his prayer things, and I sat at a little distance from him until he finished praying. Not once did he ask me why I did not pray, too. The only time we spoke about it was when I brought up the subject.

“Have you always prayed three times a day?” I asked.

“Not always, but once I started I have not let off.”

“How did you manage in South Africa?”

“As best I could. One time, I managed to get a little free time when we were in the jungle, or bush, as they call it. I walked toward the river in order to be some distance from the other soldiers. I found a spot I liked and I said my prayers. At the part where we step back and then forward again, I felt myself step upon something that moved. I did not let that disturb my prayers. After I finished, I looked around, and there lay a crocodile. It had not harmed me, and it made no movement toward me as I walked away, although it watched me all the time.”

“Go on. You are pulling a fast one.” I laughed.

To my surprise he leaned forward and caught my elbow in a viselike grip. “Don’t call me a liar. I do not tell lies, and if you want to be my friend do not lie to me, either. If I tell you I stepped on a crocodile, you can be sure that I stepped on a crocodile. You can find any explanation for why it happened, but do not doubt the truth of my words.” He let my arm go.

I rubbed my elbow and said, “Maybe the animal was not hungry. Just like our Indian pythons, they, too, can go without food for months once they have a bellyful of some animal.”

“I will not argue with your belief. You may be right. I prefer to believe that the Lord saved me because of my daily devotions to Him.”

“I wish I could believe and pray like you do,” I said.

“Don’t worry. When the Lord decides to grab you, you will not be able to run away. You will return to the fold quietly and willingly.”

We never spoke about religion or prayer after that. We told each other everything about ourselves and our families. Then we came to the joint decision that it was time to get married. We had both had close brushes with death, so we saw the importance of having children. It would not be difficult to find brides from the villages the Bene Israel inhabited along the Konkan Coast. We had regular work, which promised a pension in old age. This was security. What else could a father want for his daughters? I was twenty-three years old, and Joseph was twenty-one. We had a future with the British Army. We considered ourselves to be suitable bridegrooms, the kind any girl would desire.

The ship docked at Bombay, but we were not free to look for girls. We had to go to a military hospital first. Army ambulances met us at the docks and took us to the big railway station called Victoria Terminus. A train waited for us there. Every wagon had a large red cross painted on both its sides. We were taken to a big military rehabilitation hospital in Deolali. This is where we met Subahdar Samuel Kolet.

Samuel Kolet was around forty-five years old. He was in charge of the medical stores. We recognized him for a fellow Bene Israel from the moment we saw him. Because Joseph wanted information about the local synagogue, we spoke to him immediately. He told us that there were very few Jewish families in the city and they had no synagogue because few of the men prayed three times a day. During festivals and on Shabbat they got together for prayers, and we were welcome to join them. He invited us to his house for kiddush and dinner on Friday night.

Dinner at Subahdar Kolet’s house changed our lives forever. He had seven children, and two of his daughters were of marriageable age. Elisheva was eighteen years old, and Ketura was sixteen. I caught one glimpse of Ketura and knew that my future lay with her. She was not exactly beautiful, but she had a certain grace and charm that overpowered me. Her eyes were large, her smile shy, and her hair fell almost to her knees. She had high cheekbones and a dimple in one cheek. I watched her, and Subahdar Kolet watched me. I was not aware of this at the time. It was Joseph who brought it to my attention.

“You made an ass of yourself,” he said when we were back in our hospital ward. “We will be lucky if he invites us again. Why did you have to stare as though you have never seen a woman in your life?”

“Simple,” I answered, a bit annoyed at being called a donkey. “I haven’t seen a girl like her before.”

“She is just another ordinary-looking girl.”

“That may be so, but I intend to marry her.”

“Congratulations. In that case the subahdar has no reason to be angry. He cannot refuse such a good match for his daughter. You are also wise in your choice. She is familiar with the life an army family leads. The adjustment will be no adjustment at all.” Joseph was sure that everything would work out for me.

I was not so sure. “You are right, Joseph, but there is a problem. Ketura is the younger of the two girls. The father will want the elder girl to be married first. I do not really want to wait,” I said.

“No problem. What are friends for? I’ll marry the elder one,” he said. “What is she like? I was too busy watching the drama you put on to notice the other girl.”

“She is small, slim, and pretty. Her hair falls only to her waist, long, but not really long like Ketura’s. Her eyes are a lighter brown than her sister’s, and her skin is lighter, too. Her nose is a bit upturned. She has pretty hands and feet,” I replied.

“You saw a lot for a man who had eyes only for the younger girl.” Joseph laughed.

The next day we searched for Subahdar Kolet during the hour we were supposed to be at the swimming pool. We found him in a storeroom counting a new consignment of red army hospital blankets. He pointed to a bench and asked us to sit there until he finished his work. We saw that he was doing nothing that he could not lay aside for a few minutes, so we assumed that he knew what we, or at least I, wanted. He was establishing his right to exert authority over us. We both took this as a positive sign.

We roasted in the Deolali sunshine. There were other benches at a distance under shady mulberry trees, but we had been asked to sit where he could watch us. It was in our interest to comply with his wishes. After about forty minutes he made his appearance and immediately took us to the veranda of the VD ward. He wanted to sit in the shade. We mopped our foreheads and necks with our handkerchiefs while he watched us with a smile. I was hesitant, but Joseph, true to his nature, came straight to the point.

“Hum ladkaiyon ka hath manganye ayie hain. We have come to ask for the girls’ hands in marriage,” he said.

“Ladkaiyon? Girls? You mean both?” he asked.

“Yes,” Joseph said.

“Give me your home addresses and the names of your commanding officers with their addresses. I must make inquiries before I decide,” Kolet said.

This was a reasonable request. It was also what custom demanded. Joseph and I knew that sometimes a bride’s father makes the groom wait for no reason at all. Our sojourn on the bench was enough for us to put Kolet in this category.

“We have only nine weeks left of our stay in the hospital here. If the answer giving and wedding are not over by then, I shall leave and look for another girl. It is not as though we are in love with the girls, and I for one cannot afford to travel back and forth,” Joseph said.

“You have just returned wounded from the war in Africa. You have money.”

“Not to waste it on silliness, I haven’t. I come from a large family that I help support. You must realize, Subahdar sahib, that I am a man of my word. What I have said I have said. I will not spit and then lick it up. I tell you I will not waste time or money for no sensible reason.”

Joseph’s outspokenness made me fear that I had lost my chance to get Ketura. I cleared my throat to say something soothing, but Joseph barged in again.

“Bentzion has offered for Ketura and I for Elisheva. I am younger than he is. This should be clear before you start making inquiries. Is there something else you wish to ask us?”

Kolet had nothing to ask, so we rose and went to the swimming pool. We spent a lot of time in the pool during the next two weeks. We were not invited to the Kolet house during this period. The subahdar had disappeared from the hospital. I made inquiries about his whereabouts when Joseph was in the gymnasium with the doctors. I knew that he would not bend under any pressure Kolet tried to exert. He told me that he thought Kolet was an ass who would let a little power go to his head and make him into a tyrant. Joseph was not going to let him make things difficult for us. I was a different proposition altogether. I was nervous and anxious. I do not know how much of it was due to love, but my pride was also involved. A refusal would be a comedown in my self-image.

The man who replaced Kolet in the storeroom told me that Kolet had taken three weeks of compassionate leave to deal with family problems.

“Is something wrong?” I asked.

“No, no. He is looking into the matter of two matches offered for his daughters.”

“That’s nice,” I said. “What does he say about the matches?” I added as casually as I could.

“He is hoping for the best, although one of them seems to be a bit of an akadoo, a stiff, stubborn person. Still, if you think about the size of his community, who can blame him for being anxious about his daughters?”

I had heard enough. I knew that the girls were ours. We just had to wait until Kolet returned from his visits to our homes and those of our friends. Our commanding officers would be prompt in their approvals. The officers took as much care of their men as they could, and neither of us had a blemish on his army records. They would also feel that they owed something to the men who were wounded in action.

We kept ourselves busy with exercise and visits to the recreation room, where we played cards and carom. I became quite good at darts, while Joseph made use of the library. I was not one for reading much, but he was quite a scholar. He read in Marathi, Gujarati, and English. An Irish soldier named Peters spent hours discussing books with him, while I played games of solitaire, not understanding a word of the discussions that I listened to with only half an ear.

Subahdar Kolet appeared at our breakfast table about two weeks after our last conversation with him. “You are invited to my house for dinner this evening. Be there by seven o’clock,” he said before he turned on his heel and almost marched out.

Joseph and I applied to the duty officer for passes. We usually had to be back by ten o’clock, but Joseph decided that we needed more time. He told the officer that we were expecting to be given answers for offers we had made for the girls we intended to marry. The officer laughed and gave us passes until midnight. “The CO will kill me, but good luck,” he said as he shook hands with both of us.

“You have some cheek,” I said to Joseph when we were outside the hospital gates that evening. “You know that the doctors want us to be in bed by ten o’clock at the latest.”

“Truth has its own charm,” he replied with a big smile. “I had nothing to lose if he had said no, but it was worth a try. Now we will not have to hurry.”

Joseph bought a packet of pedas, the sweetmeat that is usually distributed when an engagement is announced. He divided it into two small packets that could fit into his trouser pockets. “I don’t want to insult the family by seeming overconfident,” he explained. “When the answer is given, I will do the mooh meetha....

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSchocken

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 0805242481

- ISBN 13 9780805242485

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages256

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Dropped from Heaven: Stories

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Dust Jacket Condition: New. 1st Edition. Seller Inventory # 006575

Dropped from Heaven: Stories

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 0.9. Seller Inventory # 0805242481-2-1

Dropped from Heaven: Stories

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 0.9. Seller Inventory # 353-0805242481-new

DROPPED FROM HEAVEN: STORIES

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.9. Seller Inventory # Q-0805242481