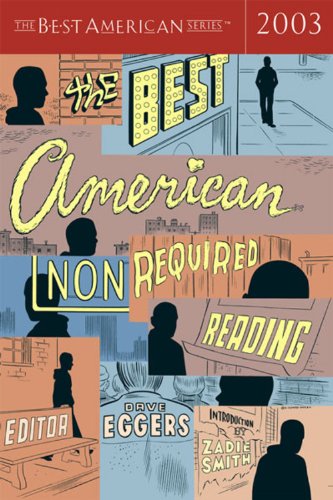

Items related to The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2003

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

DAVE EGGERS is the editor of McSweeney’s and a cofounder of 826 National, a network of nonprofit writing and tutoring centers for youth, located in seven cities across the United States. He is the author of four books, including What Is the What and How We Are Hungry.

For young readers and young writers, here are half a dozen commonplaces concerning the act of reading, required or otherwise:

1. Dr. Johnson: A man ought to read just as inclination leads him; for what he reads as a task will do him little good.” In principle I agree with this but I’m not quite this sort of reader. Not confident enough to be this reader. Inclination” is all very well if you are born into taste or are in full possession of your own, but for those of us born into families who were not quite sure what was required and what was not well, we fear our inclinations. For myself, I grew up believing in the Western literary canon in a depressing, absolutist way: I placed all my faith in its hierarchies, its innate quality and requiredness. The lower-middleclass, aspirational reader is a very strong part of me, and the only books I wanted to read as a teenager were those sanctified by my elders and betters. I was certainly curious about the nonrequired reading of the day (back then, in London, these were young, edgy men like Mr. Self and Mr. Kureishi and Mr. Amis), but I didn’t dare read them until my required reading was done. I didn’t realize then that required reading is never done.

My adult reading has continued along this fiercely traditional and cautiously autodidactic path. To this day, if I am in a bookshop, browsing the new fiction, and Robert Musil’s A Man Without Qualities happens to catch my eye from across the room, I am shamed out of the store and must go home to try to read that monster again before I can allow myself to read new books by young people. Of course, the required nature of The Faerie Queene, books 3 through 10 of Paradise Lost, or the Phaedrus exists mostly in my head, a rigid idea planted by a very English education. An education of that kind has many advantages for the aspiring writer, but in my case it also played straight and true to the creeping conservatism in my soul. Requiredness lingers over me. When deciding which book of a significant author to read, I pick the one that appears on reading lists across the country. When flicking through a poetry anthology, I begin with the verse that got repeated in the .lm that took the Oscar. I met an Englishwoman recently, also lower middle class, who believed she was required to read a book by every single Nobel laureate, and when I asked her how that was working out for her, she told me it was the most bloody miserable reading experience she’d ever had in her life. Then she smiled and explained that she had no intention of stopping. I am not that bad, but I’m pretty bad. It is only recently, and in America, that the hold required reading has had on me has loosened a little.

Tradition is a formative and immense part of a writer’s world, of the creation of the individual talent but experiment is essential. I have been very slow to realize this. Reading this collection made me feel the literary equivalent of Zadie, honey, you need to get out more”; I began to see that interesting things are going on, more and more things, and that I can’t keep up with them, and that many of them cause revolt in the required-reading part of my brain (I get very concerned by the disappearance of some of the more expressive punctuations: the semicolon, the difference between long and short dashes, the potential comic artfulness of the parentheses), and yet, I so enjoyed myself that even if what I have read in this book is the clarion call of my own obsolescence, it seems essential to defend experiment and nonrequiredness from those who would attack it.

Thing is, the very young and very talented are not beholden. Nor are the readers who would approach them. The great joy of nonrequiredness seems to me that as a young reader, you have this opportunity to hold opinions that are not weighed down by the opinions that came before. It is up to you to measure the worth of the writers in your hand, for you are young and they are young and actually I am still young and we are all in this thing together. And I feel pride when I see that, collectively, we are not only writing and reading weird stories, but also writing and reading serious journalistic nonfiction and comics and satire and histories, and we are doing all these things with the sort of rigor and attention that no one expected of us, and we are managing this rigor and attention in a style entirely different from our predecessors’. We are so good, in fact, that we cannot hope to stay nonrequired very long. We, too, will soon become required, which comes with its own set of problems.

2. Logan Pearsall Smith: People say that life is the thing, but I prefer reading.” How important is the touch of the real”? Should the young man hankering after a literary life read through his massive dictionaries or stand upon a pile of thhhhhem to reach the high shelf where the whiskey is kept? When I was in my teens, making a few stabs at writing, I had a very low opinion of experience. It did not seem to me that trekking to the cobwebbed corners of the world for six months and returning with a pair of ethnic trousers made anybody a more interesting fellow than when they left. Weary, stale, .at, and unprofitable were all the uses of the world to me which meant, of course, that I was not much good at anything and had no friends. No matter what anybody says, it is a mixture of perversity and stomach-sadness that makes a young person fashion a cocoon of other people’s words. If the sun was out, I stayed in; if there was a barbecue, I was in the library; while the rest of my generation embraced the sociality of Ecstasy, I was encased in marijuana, the drug of the solitary. It was suggested to me by a teacher that I might write about what you know, where you live, people you see,” and in response I wrote straight pastiche: Agatha Christie stories, Wodehouse vignettes, Plath poems all signed by their putative authors and kept in a drawer. I spent my last free summer before college reading, among other things, Journal of the Plague Year, Middlemarch, and the Old Testament. By the time I arrived at college I had been in no countries, had no jobs, participated in no political groups, had no lovers, and put myself in no physical danger apart from an entirely accidental incident whereupon I fell fifty feet from my bedroom window while trying to reach for a cigarette I’d dropped in the guttering. In short, I was perfectly equipped to go on to write the kind of fiction I did write: saturated by other books; touched by the world, but only very vicariously. Welcome to the house that books built: my large rooms wallpapered with other people’s words, through which one moves like a tourist through an English country manor somewhat impressed, but uncertain whether anyone really lives there.

These days, given the choice between a week in the Caribbean and a week reading A High Wind in Jamaica, I would probably still choose the book and the sofa. But this is no longer a proud rejection, only a stiffened habit. To read many of the pieces in this collection is to discover the uses of the world, of experience, is to be shown how life can indeed be the thing, if only you let it. I am impressed by this strong, noble, journalistic trend in American writing, to be found in this very book, dispassionately exercising itself over Saddam’s daily existence, or what it is like to live in South Central L.A. I had never met with this kind of journalism until I came to America. It has since been explained to me that most Americans read In Cold Blood when they are fifteen, but I read it only two years ago, and not since Journal of the Plague Year had I felt writing like that, and I mean felt it; writing that gets up inside you, physically, giving you back the meaning of the word unnerve. When you read too many novels, and then when you happen to write them as well, you develop a sort of hypersensitivity to the self- consciously literary” as it manifests itself in fictional prose it’s a totally irrational, violent, and self-defeating sensitivity, and you know that, but still, every time you see it, including in your own stuff, it makes you want to scream. So to read what purports to be the truth no matter how decorated feels to me like the palate-cleansing green tea that follows a busy meal of monosodium glutamate.

The point is, my mind has changed about experience. I thought I didn’t like memoirs, I thought I didn’t like travelogues, I thought I didn’t like autobiographical books written by people under forty, but the past three years of American writing have proved me wrong on all these counts. It is never too late to change your mind about what you require. I see now that I am required, and more than this, that I require, I need, to do something else with my life than solely to read fiction and write it. I’ve got to get out there, abroad and up close; I’ve got to smell things, eat them, throw them across a park, sail them, dig them up, and see how long I can survive without them, or with them.

As I write this, I am at a college with a novelist younger than me, and at a recent lunch he put before me a hypothetical choice. Should a young man stay the university distance for those four long years? Or should he drop out and seek the experiences that are owed him? Which decision makes the better writer? I argued the case for college, listing the writers on my side of the Atlantic who stayed the course even while indulging in such various activities as storing a bear in their room (Byron), ditching class to walk up hills (Wordsworth), spending most of the time having suits made (Wilde), stopping soccer balls at the goal’s mouth (Nabokov), or scribbling obscenities in library books (Larkin). He naturally countered with all the Americans who quit while they were ahead, or earlier (Mark Twain, William Faulkner, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Jack London). He won the argument because I had no experience with which to argue against it. By definition Emersonian experience cannot be rejected without any experience of it; it must be passed through and felt and only then compared to the Miltonic experience: the dark room, a book, the smell of the lamp. I’m not qualified to make the judgment, no, not yet although I intend to be. I want to travel properly next year. See some stuff. In the meantime, maybe we should heed the advice of the Web site www.education- reform.net/dropouts.htm and Shaun Kerry, M.D. (diplomate, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology), who comes down firmly on the side of life:

Ultimately, what distinguishes the aforementioned individuals from the rest of us is their passion for learning that transcends the structured environment of the classroom. Instead of limiting their education to formal schooling, they were curious about the world around them. With their fearless spirit of exploration and their desire to experiment, these individuals discovered their true passions and strengths, which they built upon to achieve success later in life.

Imagine what a loss for the world it would have been if Walt Disney had confined his learning to the requirements of his school’s curriculum, and followed only the guidance of his teachers, rather than his own internal motivation. His extraordinary animated features may have never been created.

Imagine.

3. Laurence Sterne: Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine; they are the life, the soul of reading.” Yet, somehow, digressions have gone and got themselves a bad name. The name might be indulgence. Digressions, supposedly, are for writers who cannot control themselves, or else writers who seek to waste the hard-earned time of the no-bullshit reader who has little patience for frippery. The attitude: Writer, do not take me down this strange alley when I mean to get from A to B, and don’t think that, just because I am from the Midwest or Surrey, I’ll allow some New York or London wiseass to take me on an unnecessary, circuitous journey and charge me too much while they’re at it. And less of the chat I don’t need a tour guide Christ, I know this city like the back of my hand. And please note that I’m man enough to use honest language like back of my hand,” which is more than you can say for these namby-pamby writers.

And then on the other side of the street, you’ve got your folks who care only for digression. They don’t feel they’ve got their money’s worth unless, while trying to get from Williamsburg to the Upper East Side, the writer takes them by way of Nairobi, a grandparent’s first romance, the Guadeloupean independence struggle of the 1970s, through the stink of the Moscow sewer system and up through the bud-mouth of an unborn child. But these folks are few.

Among the majority, digression has fallen from favor, along with many of the great digressors, of which Sterne was the mighty progenitor. Maybe digression” has been confused and twinned with complexity,” but if that’s so, then someone should explain that a path off a main road needn’t be busy or populated it can be plain, flat, straight, almost silent. But for all digressions to be of this kind would seem to me a shame. To be so strict about it, I mean. I do like a sunny, busy lane. And I like a memory-saturated, melancholic one as well. I think of W. G. Sebald’s The Emigrants, that ode to digression, structured like a labyrinth of lanes leading away from a historical monument that is itself too painful to be looked at directly. This might be a model. Things are so painful again just now.

Maybe I worry too much about these things, but like a silent minority of transvestite schoolboys and wannabe drag kings, I imagine a whole generation of not-yet-here writers who feel great shame when contemplating their closet full of adjectival phrases, cone-shaped flashbacks, multiple voices, scraps of many media, syzygy, footnotes, pantoums. I worry that they will never wear them out for fear of looking the fool.

Look: Wear your black some days, and wear your purple others. There is no other rule besides pulling it off. If you can pull off, for example, blocks of red and yellow in horizontal stripes, feathers, tassels, lace, toweling, or all-over suede, then for God’s sake, girl, wear it.

Here is a beautiful digression from a master digressor. He is meant to be discussing his sixteen-year-old cousin, Yuri:

He was boiling with anger over Tolstoy’s dismissal of the art of war, and burning with admiration for Prince Andrey Bolkonski for he had just discovered War and Peace which I had read for the first time when I was eleven (in Berlin, on a Turkish sofa, in our somberly rococo Privatstrasse flat giving on a dark, damp back garden with larches and gnomes that have remained in that book, like an old postcard, forever).

4. James Joyce: That ideal reader suffering from an ideal insomnia” The ideal reader cannot sleep when holding the writer he was meant to be with.

Sometimes you meet someone who is the ideal reader for a writer they have not yet heard of. I met a boy from Tennessee at a college dinner who wore badly chipped black nail polish and a lip ring, had perfect manners, and ended any disagreement or confusion with the sentence Well, I’m from Tennessee.” He was the ideal reader for J. T. Leroy and did not know it, having never heard of him. This was a very frustrating experience. Multiple recommendations did not seem sufficient I wanted to take him at that moment, in the middle of the dinner, to the bookstore so he might meet the two novels he was going to spend the rest of his life with.

A cult book, of course, is one that induces the feeling of being chosen as ideal” in every one of its readers. This is a rare, mysterious quality. The difference between, for example, a fine book like Philip Roth’s The Human Stain and a cult book like J. D. Saling...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin

- Publication date2003

- ISBN 10 0618390731

- ISBN 13 9780618390731

- BindingAudio CD

- EditorEggers Dave

- Rating

Shipping:

US$ 9.78

From Germany to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Best American Nonrequired Reading 2003

Book Description Gut/Very good: Buch bzw. Schutzumschlag mit wenigen Gebrauchsspuren an Einband, Schutzumschlag oder Seiten. / Describes a book or dust jacket that does show some signs of wear on either the binding, dust jacket or pages. Seller Inventory # M00618390731-V

The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2003

Book Description Audio CD. Condition: Good. 3 Reliable AUDIO CDs, polished for your satisfaction, withdrawn from the library collection. Some library sticker and stamp to the set. We will clean the CDs for a worthwhile listening experience. Enjoy this presentable AUDIO CD performance. Audio Book. Seller Inventory # 121509152014226

The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2003

Book Description Condition: Good. SHIPS FROM USA. Used books have different signs of use and do not include supplemental materials such as CDs, Dvds, Access Codes, charts or any other extra material. All used books might have various degrees of writing, highliting and wear and tear and possibly be an ex-library with the usual stickers and stamps. Dust Jackets are not guaranteed and when still present, they will have various degrees of tear and damage. All images are Stock Photos, not of the actual item. book. Seller Inventory # 32-0618390731-G