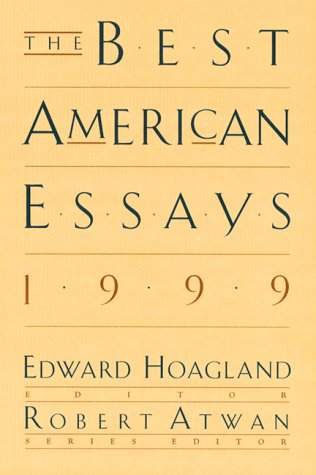

Items related to The Best American Essays 1999

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Essays are how we speak to one another in print - caroming thoughts not merely in order to convey a certain packet of information, but with a special edge or bounce of personal character in a kind of public letter. You multiply yourself as a writer, gaining height as though jumping on a trampoline, if you can catch the gist of what other people have also been feeling and clarify it for them. Classic essay subjects, like the flux of friendship, "On Greed," "On Religion," "On Vanity," or solitude, lying, self-sacrifice, can be major-league yet not require Bertrand Russell to handle them. A layman who has diligently looked into something, walking in the mosses of regret after the death of a parent, for instance, may acquire an intangible authority, even without being memorably angry or funny or possessing a beguiling equanimity. He cares; therefore, if he has tinkered enough with his words, we do too.

An essay is not a scientific document. It can be serendipitous or domestic, satire or testimony, tongue-in-cheek or a wail of grief. Mulched perhaps in its own contradictions, it promises no sure objectivity, just the condiment of opinion on a base of observation, and sometimes such leaps of illogic or superlogic that they may work a bit like magic realism in a novel: namely, to simulate the mind's own processes in a murky and incongruous world. More than being instructive, as a magazine article is, an essay has a slant, a seasoned personality behind it that ought to weather well. Even if we think the author is telling us the earth is flat, we might want to listen to him elaborate upon the fringes of his premise because the bristle of his narrative and what he's seen intrigues us. He has a cutting edge, yet balance too. A given body of information is going to be eclipsed, but what lives in art is spirit, not factuality, and we respond to Montaigne's human touch despite four centuries of technological and social change.

Montaigne's Essais predated by a quarter-century Cervantes's Don Quixote, which was probably the first novel. And the form of composition Montaigne gave a name to would not have lasted so long if it were not succinct, diverse, and supple, able to welcome ideas that are ahead of or behind the blurring spokes of their own time. But whereas a novelist is often a trapezist, vaulting from book to book, an essayist is afoot. Not a puppetmaster or ventriloquist, he will sound recognizable in his next appearance in print. There is a value to this, though Don Quixote as a figure outshines any essay. Imperishably appealing, he is an embodiment, not speculation, and we can simply call him to mind, much as we remember Conrad's Kurtz, in Heart of Darkness, and Dickens's Oliver Twist, although the regimes up the Congo River and in London aren't now the same.

An essayist's materials are drawn primarily from his or her own life, and he knits a skein of thoughts and impressions, not a made-up tale. An epic drama such as King Lear is thus not his province even to dream about. His work is humbler, and our expectations of him are less elastic than of novelists or poets and their creations. They can flame out in a flash fire, surreal or villainous, if the story is compelling or the language smacks a bit of genius. We accept different behavior from Céline or Genet, Christopher Smart or Ezra Pound, than from Dr. Johnson. Norman Mailer can stab his wife and William Burroughs can shoot his, and somehow we don't blanch. They "needed to," one hears it said. Their imaginations must have got the better of them. But if an essayist had done the same it would have queered his legacy. He is supposed to be the voice of reason. Though modestly chameleon as a monologuist (and however much he wants to recalibrate it), he is an advocate for civilization. He doesn't murder a foe in the street, like the sculptor Benvenuto Cellini, or get himself slain in a tavern brawl, like the playwright Christopher Marlowe, or gut-shot, like John Ruskin, in a duel. A murderer or madwoman quarantined in a book on the bedside table can provide excitation and cautionary reading, but an essayist, being his own protagonist, should be faceted rather like a friend. We might give him our keys and put him up in the guest room. He won't be stealing the silverware and debauching the children, and, after sleeping on our problems, he will sit at the breakfast table in the morning sunshine and tell us what we ought to do. Or, at the outside, if - like the master essayist Charles Lamb - his sister has slaughtered his mother, he will devote the next thirty-odd years to piecing together a productive existence for himself and her, not despairing like an afficionado of the Absurd.

Essayists are not Dadaists, and in the endgame that may be in progress - with our splintering attention span, our hiccccccuping religions, staccato science, and spinning solipsism - they may prove useful. Do we human beings have a special spark of divinity? And if so, as we mince our habitat and compress ourselves into ever tighter spaces, having always claimed that there couldn't be too much of a good thing, how many of us are finally going to constitute a glut of divinity? Judeo-Christianity hasn't said. Nor did "the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God," which Thomas Jefferson invoked at the beginning of our Declaration of Independence. Or Emerson's rapturous prescription in Nature in 1836 (Emerson being the other founding father of essay writing in America) that an intelligent observer should become "a transparent eye-ball . . . part or particle of God," amid nature's ramifying glory. Now, man threatens to become a divinity doubled, redoubled, and berserk ad nauseam. However, the essay's brevity, transparency, and versatility should suit this age of reconsideration.

Essays are a limited genre because the writer will suggest that life is more than money, for example, without inventing Scrooge; that brownnosing demeans everybody, without the specter of Uriah Heep. Candide, Starbuck, Injun Joe, Moll Flanders and Becky Sharp led lives more far-fetched than an essayist's, whose medium is mostly what he can testify to having seen or read. Working in the present tense, with common sense his currency, "This is what I think," he tells the rest of us. And even if he speaks about alarming omens, we feel he'll be around tomorrow, not leap headlong into life and burn to a crisp at thirty-two or twenty-eight, like Hart Crane or Stephen Crane, or wind up forlorn in a railroad station fleeing his wife, as Tolstoy did when dying. The limitations are reassuring as well as tethering.

James Baldwin didn't metamorphose into an arsonist or a rifleman when he warned against race war in The Fire Next Time. And George Orwell deconstructed colonialism in essays considerably more nuanced than Heart of Darkness - supplementing though not supplanting Kurtz's immortal line "The horror! The horror!" In a way, it's easier to visit a headwaters area of the Nile or Congo and find conditions not substantially improved since independence when you've read Orwell as well as Conrad on human nature, because these nuances prepare you better for disillusion. Conrad's picture was so stark, surely never again would the world see comparable scenes!

Ripples sway us - traffic tie-ups on a cloverleaf, on-line stock swings, revenge-of-the-rain-forest viral escapees - at the same time that our proud provincialism is called upon to bend the mind around Islam's surging claims, Latino vigor and disorder, chaos in Africa, and a Chinese-puzzle future. In a famine belt along the upper Nile, I've seen child-sized raw-dirt graves scattered everywhere beside a poignant web of paths of the sort that starving people pace. A scrap of shirt or broken toy was laid on top of each small mound to personalize the spot; and hundreds of bony, wobbling children who had survived so far ran toward me (a white-haired white man) to touch my hands in hopes that I might somehow be powerful enough to bring in shipments of food to save their lives. Their urgent smiles were giddy or delirious in skulls already outlined under tightened skin - though they were fatalistic, almost docile, too, because so many adults had told them for so many weeks that there was nothing to eat and so many people whom they knew had died. I interviewed the Sudanese guerrilla general who was in charge of protecting them about what could be done, but he was delayed a little that afternoon because (I found out later from an Amnesty International report) he had been torturing a colleague by pounding a nail through his foot.

Now, essayists in dealing with the present tense are stuck with the nuts and bolts of what's going on. And what do you say about that endgame on the Nile, which I believe was a forerunner, not an anomaly? I expect an epidemic of endgames and disintegration in other forms. Essayists will become "journeymen," in a new definition for that hackneyed term: out on the rim, seeing what's in store. The cataract of memoirs being published currently may be a prelude to this - memoirs of a cascading endgame. Yet essayists are not nihilists as a rule. They look for context. They feel out traction. They have a stake in society's survival, breaking into the plot line of an anecdote to register a reservation about somebody's behavior, for instance, in a manner that most fiction writers would eschew, because an essayist's opinions are central, part of the very protein that he gives us. Not omniscient like a novelist, who can create a world he wants to work with, he has the job of finding coherence in the world that we already have. This isn't harder, just a different task. And he usually comes to it in middle age, having acquired some ballast of experience and tested views - may indeed have written several novels, because of the higher glamour and freedom of that calling. (For what it's worth, I sold my first novel at twenty-one and wrote my first essay at thirty-five.) "Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth," as Picasso said; and to capture within an imagined story some petal of human longing and defeat is an achievement irresistibly appealing. Essayists, by denying themselves that license to extravagantly fudge the facts of firsthand observation, relegate themselves to the Belles Lettres section of the bookstore, neither fiction nor journalism, because they do partly fudge their reportage, adding the spice of temperament and a lifetime's favorite reading. And if an enigma seems a jigsaw, they will tend to see a picture in it: that life therefore is not an oubliette. The fracases they get into are on behalf of democracy, as they see it (Montaigne, Orwell, and Baldwin again are examples), and their iconoclasm commonly leans toward the ideal of "comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable," which journalists used to aspire to. Like a short-story writer, an essayist is after the gist of life, not Balzacian documentation. And, like a soothsayer with a chicken's entrails, he will spread his innards out before us to discern a pattern. Not just confessional, however, a good essay is driven by the momentum of an inquiry, searching out a point, such as are we divine? - an awfully big one for a lowly essayist, but it may be the question of the coming century.

Essayists also go to the fights, or rub shoulders on the waterfront, get divorced ("Ouch," says the reader, "that was like mine"), nibble canapés, playing off their preconceptions of a celebrity or a politician against reality. They will examine a prejudice (is this piquant or ignoble, educated or soggy?) or dare a pie in the face for advancing an out-of-fashion idea. Or they may simply saunter, in Thoreau's famous reading of the word: r la Sainte Terre, to the Holy Land, or sans terre, at home everywhere - maybe only to the public library to browse among dead friends. Although a novelist can blaze along on impetuous obsessions and we will follow if Scheherazade has set her cap to catch us (and then what happened?), an essay is a current of thoughts corduroyed with sensory impressions, an author afoot, solo, with no movie sale in the offing or hefty hope of fame. Speaking his mind is likely to be a labor of love, and risky because if a work of fiction flops, at least it's nominally somebody else's persona that has been boring the reader.

A solo voice welling up from self-generating sources, or what Thoreau once called an "artesian" life, has not been the dominant mode of expression for the past half-century, so most of the best essays have had to find a home in magazines of lesser circulation, like Harper's, the Village Voice, the American Scholar, Outside, Yale Review, or the Hungry Mind Review. The first-tier publications had corporate styles and personalities, each one insisting upon its editorial "we." But recently publishing has met with such a swirl of confusion that even flagship magazines have been losing money or grandiosity and wondering what tack to take. Essays are reappearing in unexpected places, in National Geographic as well as The New Yorker, and on the airwaves and in newspapers, as corrective colloquy or amusing "occasionals." Paralleling the flood of memoirs that are coming out, the essay form is in revival. And the two genres do overlap, though for essays a narrative is not an end in itself, as it can be in a memoir.

A sense of emergency, I suspect, is powering the popularity of memoirs, the urge for quicker answers than we get from reading novels: What's happening? How shall we live? Nature, which Jefferson and Emerson regarded as central to the health of society, is lately treated as a kind of dewclaw on our collective consciousness. This will, I think, begin to change in the face of ecological catastrophes, and essayists will be in on the action again - as they have attacked so many problems before, from slavery to political tyranny, in the struggle to preserve civilization from itself. (War is a "human disease," Montaigne said.) The most civil of the literary arts, yet also a "book of the self," "spying on the self from close up," essays are versatile enough that in the same piece, "Of Experience," in which Montaigne says that "death mingles and fuses with our life throughout," he tells us that he can't make love standing up and speaks considerably about his kidneys, urination, and bodily "wind." Wholehearted, supple, an essayist over time may tell you everything you might want to know about him and stretch that measurement a bit, the way a friend or spouse or partner gradually does, until nothing about the living package of that person turns you off. If you know the anguish, joy, and bravery somebody has experienced, you can also share their episodes of shame and indigestion.

Like you, an essayist struggles with the here and now, the world we have, with sore and smelly feet and humiliation, a freethinker but not especially rich or pretty, and quite earthbound, though at his post. Like Thoreau later on (according to Emerson's report), Montaigne says that at a dinner party, "I make little choice at table, and attack the first and nearest thing." He is not much for show and affectation, but nonetheless he eats so zestfully he sometimes bites his own fingers. In a nutshell, maybe that is how to live. Eat of life with such brio that you're not afraid to bite your fingers.

Edward Hoagland

Copyright © 1999 by Houghton Mifflin Company Introduction copyright © 1999 by Edward Hoagland

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherMariner Books

- Publication date1999

- ISBN 10 0395860555

- ISBN 13 9780395860557

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages297

- EditorHoagland Edward, Atwan Robert

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 6.65

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Best American Essays 1999

Book Description Softcover. Condition: New. Edition Unstated. Appears never used. Quantity Available: 1. Category: Essays & Literary Criticism; ISBN: 0395860555. ISBN/EAN: 9780395860557. Pictures of this item not already displayed here available upon request. Inventory No: 1560729150. Seller Inventory # 1560729150

The Best American Essays 1999

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0395860555

The Best American Essays 1999

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0395860555

The Best American Essays 1999

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0395860555

The Best American Essays 1999

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0395860555

The Best American Essays 1999

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0395860555

THE BEST AMERICAN ESSAYS 1999

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.79. Seller Inventory # Q-0395860555

The Best American Essays 1999

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0395860555