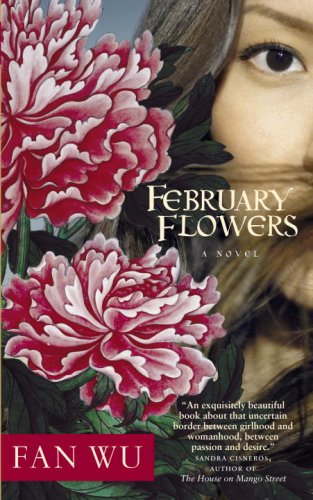

Items related to February Flowers

Set in modern China, February Flowers tells the stories of two young women’s journeys to self-discovery and reconciliation with the past.

Seventeen-year-old Ming and twenty-four-year-old Yan have very little in common other than studying in the same college. Ming, idealistic and preoccupied, lives in a world of books, music, and imagination. Yan, by contrast, is sexy, cynical, and wild, with no sense of home. Yet when the two meet, they soon become best friends. Their friendship is brief, almost accidental, but intense, and

it changes Ming’s world forever.

Insightful, sophisticated, and rich with complex characters, February Flowers captures a society torn between tradition and modernity, dogma and freedom. It is a meditation on friendship, family, love, loss and redemption, and how a background shapes a life.

From the Hardcover edition.

Seventeen-year-old Ming and twenty-four-year-old Yan have very little in common other than studying in the same college. Ming, idealistic and preoccupied, lives in a world of books, music, and imagination. Yan, by contrast, is sexy, cynical, and wild, with no sense of home. Yet when the two meet, they soon become best friends. Their friendship is brief, almost accidental, but intense, and

it changes Ming’s world forever.

Insightful, sophisticated, and rich with complex characters, February Flowers captures a society torn between tradition and modernity, dogma and freedom. It is a meditation on friendship, family, love, loss and redemption, and how a background shapes a life.

From the Hardcover edition.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Fan Wu grew up on a farm in southern China, where her parents were exiled during the Cultural Revolution. She moved to the United States in 1997 for graduate studies at Stanford University, and started writing in 2002. February Flowers is her first novel and has been translated into six languages. Her short stories have appeared in Granta and the Missouri Review. She writes in both English and Chinese, and she is currently working on a second novel and a short story collection. She divides her time between northern California and China.

From the Hardcover edition.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

From the Hardcover edition.

After my marriage ends I move to a one-bedroom apartment five blocks from the university where I studied twelve years ago. The greyish building, stuccoed, slanting slightly to the right, is a conversion from a single-family house owned by a grocery store proprietor — now the landlord — and has six units. Mine is on the top but the view is blocked by a forest of half-built commercial high-rises. The landlord wants me to sign a one-year lease, but I have only agreed to a six-month term. I know her apartment building, like other shabby two- to three-storey buildings in the neighbourhood, will be torn down and replaced by another high-rise in less than a year.

I could have lived in the more modern Tianhe District like most of my friends but I like the narrow cobblestone alley in front of the building, where old people gather in the late afternoons under a spreading banyan tree to play mahjong or sing Cantonese opera. Across the alley is another identical apartment block. All its balconies are covered with laundry and flowers such as roses, chrysanthemums, lilies and hibiscus — Cantonese people like flowers and arrange them well, often in window boxes that decorate the streets and houses, bringing a little gentle beauty to the cityscape. Sometimes a middle-aged woman appears on a balcony, yelling in Cantonese at someone in her family to return for dinner.

I wake up every morning to the sounds of my landlord chopping meat bones in her apartment across from mine. She has lived in Guangzhou from birth. She loves to cook and has taught me how to make salt-baked chicken, beef stew clay pot and shrimp wonton noodle soup. On warm days she will prepare cold herb tea and save a cup for me. After trying many different cuisines from many different regions, I have acquired a taste for Cantonese food with its mild flavour and freshness.

On weekends I sometimes go to Shamian Island to read on the beach of the Pearl River. There, all the historical Western-style mansions are well maintained, with their white stone walls, wrought-iron banisters on the balconies shaded by banyan trees, and ornate wooden doors. The sight of them makes me think of the history in the nineteenth century when the Qing Dynasty government allowed European and American businesses to set up a trading zone here. High-rises stretch along both sides of the river. The five-star White Swan Hotel is busier than ever — now a hub for foreigners adopting Chinese orphans. I often encounter white parents on the beach, holding a Chinese baby girl they are planning to take home. Once a couple from Sweden approached me and asked if I could suggest a good Chinese name for their newly adopted baby.

After living in Guangzhou for over ten years, I have begun to fall in love with this city, not just for its amiable weather, but also for the relaxation, generosity, and down-to-earth nature of its people, which wasn’t how I felt when I first came here as a student. A decade has changed the city, and has also changed me in subtle ways that reflect my age and experience. I drawl involuntarily at the end of a sentence when speaking Mandarin — my mother tongue — as a Cantonese would; I start my Sunday mornings with dim sum and cup after cup of tea at a teahouse; I buy an orange tree for New Year and hang red envelopes on its branches to be blessed with good fortune, in accordance with the old local custom. I realise that I am becoming a citizen of my adopted city, adapting and assimilating.

I am an editor at a reference and textbook publisher. The job pays well but to me it is just a job. I go to work at eight, leave at five and never stay late. After work I often stroll to Tianhe Book City next to my office to check out the latest arrivals in the literature section. Some nights I go to a bar or coffee house with my coworkers or old college friends. We talk about work, fashion, politics, the economy, or other subjects that matter or don’t matter to us. Single again, I appreciate their companionship and enjoy spending time with them. But sometimes, when I hear them talking, my mind will stray to completely unrelated thoughts, often too random and brief to be significant — perhaps about a book, a childhood incident or a unique-looking person I just saw on the street. If I let my mind wander, I always end up thinking of Miao Yan, a college friend of mine. I have not seen her for more than ten years. Though for about eleven months we were extremely close — at least I would like to think so — I now feel I know little about her and her life.

One Saturday morning, my mother calls from my hometown, a city in another province.

‘So what do you plan to do?’ she says, after asking about the weather and the cost of living in Guangzhou.

‘I have a good job and a lot of friends.’

‘You aren’t a little girl anymore. You’re almost thirty. A woman your age should be settling down by now.’

‘Ma, I did,’ I say. ‘At least I tried.’

‘You didn’t even tell your father and me until after it happened. If you had just told us and listened —’

‘You just said I’m not a little girl anymore.’ I smile. We have had this conversation a score of times. I know she will never understand no matter how often I try to explain it.

Silence on the other end. Then, ‘A friend of your father’s called him yesterday. His son was just relocated from Beijing to Guangzhou. He’s thirty-four, also divorced. No children. He’s an engineer.’ My mother clears her throat and her voice becomes soft. ‘I think you should meet him.’

‘Don’t worry about me.’

‘I don’t understand —’

‘I’m fine. I can take care of myself. Tell Baba not to worry. Nowadays, no one cares if you’re divorced or not.’ I sit down on the bed and look at myself in the full-size mirror — sleeveless black turtleneck sweater in the latest fashion, whitish low-cut jeans with yellow seams on the sides, dark brown ponytail which is shining in the sunlight from the window, and two big silver earrings dangling above delicate but well-shaped shoulders. I am startled by how much I look like Miao Yan, except for the ponytail.

‘China isn’t America,’ my mother finally says.

‘How’s Baba?’ I ask.

Next day I spend the whole morning cleaning my apartment. Like other big cities, Guangzhou has too many cars and too few trees. If I don’t wipe my desk for two days, a thin film of dust accumulates. While organising my books, I put on the phonograph an old recording of Paganini I bought at an antique store a year ago. I used to play the violin but haven’t done so since I graduated from college. Among the books is a collection of poems from university students, a few of mine included. Even after all these years I still remember some of the poems I wrote then. They tend to have a melancholy tone, obviously written by a much younger woman.

The biggest task is tidying my wardrobe. Even if I changed my clothes twice a day for a month, it would still leave a lot unworn. I got into the habit of shopping in my senior year at university, at first purely for job interviews, but over time it became an indulgence, resulting in my overstocked walk-in wardrobe.

The white box is lying in the corner like an ice cube. It contains a black dress with straps made of shiny material, and a flower-patterned silk blouse. They used to belong to Miao Yan but are mine now. I dust the box and put it back.

In the afternoon I visit the university’s Alumni Administration Office. I am applying for graduate school in the US and need transcripts for my application. As I wait in the lobby for the documents to be signed and sealed, a woman in her early thirties joins me. She is wearing a crimson pants-suit with a pearl necklace, looking as though she has come straight from an interview. She says she needs her transcripts to get to Canada, where she is emigrating with her husband and five-year-old daughter.

‘I’ve been taking cooking classes,’ she says, shrugging like a Westerner. ‘I hear chefs make more money than librarians. Who’d hire me as a librarian in Canada anyway?’

‘Did you study library and information science?’

‘Yes, from eighty-nine to ninety-three.’

‘I was a first-year student in ninety-one,’ I say, thinking about how different the university was back then. Now it is like the centre of the city. The buses to downtown run around the clock and every week a seafood restaurant opens nearby. Students ride their bikes while talking on their cell phones.

The woman walks elegantly to a long table, pours water from a glass jug into a small paper cup, and sips it.

When she sits, I ask, ‘Do you know Miao Yan?’ My heart is pounding suddenly.

‘Sounds familiar.’

‘You were classmates.’

‘Oh, that tall girl! She’s from Sichuan, isn’t she?’

‘No. Yunnan.’

‘Maybe you’re right.’ She looks at me with curiosity. ‘How did you know her?’

‘Just coincidence. Have you seen her? Do you know where she is?’

‘Not really. We were never close. She was always on her own. I doubt she was friends with any of her other classmates.’

The administrator calls her name. She stands up, smoothing her jacket and pants. Before going inside she turns abruptly at the door. ‘Now I remember. She moved to the US a few years ago. I don’t know how she did that. Anyway, someone said she met her at a boutique store in San Francisco’s Chinatown last year. Believe it or not, she owned the store.’

I thank her and wish her good luck with the emigration.

That night I can’t sleep. The past fills me with deep emotion. I recall the evening Miao Yan and I first talked. The details return with such vividness that it seems as if I am watching a video of it — the low-hanging moon, the whitish cement ground, Miao Yan’s glittering eyes, her fluttering blouse, the way she lit her cigarette and exhaled the smoke. It is all imprinted on my memory and can never be removed.

After allowing these memories to consume me for a time I can’t measure accurately, I get up and take the white box from the closet. I put on the black dress in the bathroom — it still fits perfectly. There in the mirror, I stare at myself for the longest time. In the mirror, in my eyes, I see Miao Yan and more and more of myself at seventeen.

--

‘Noodles. Chef Kang brand. Fifty fen a bag.’

One Sunday afternoon a girl knocked on the open door of my room with a broad smile, a white cardboard box between her legs, a thick stack of money in her other hand. A few streaks of sweat anchored her splayed long hair to her rose-coloured cheeks.

‘Are you from the Student Association?’ my roommate Pingping asked, her eyes narrowed with scepticism.

‘No, but they sell Chef Kang for sixty fen a bag. You do the arithmetic.’ The girl flipped her hair behind her back and crossed her arms.

‘Who knows if your noodles really are Chef Kang?’ Donghua, another roommate of mine, poked her head out of her mosquito net — she had been knitting a sweater on her bed since noon. A week ago, she had bought a few bags of knock-off Kang noodles from a street vendor and had diarrhoea for three days.

‘I don’t carry around this box for nothing. Forget it.’ The girl bent over, picked up the box, placed it on her lifted right knee and pushed it up to her chest. The metal-tipped spikes on the high heels of her black leather shoes glittered in the sunlight.

Before she walked to the next room, I put down the book I was reading and said, ‘Give me ten bags.’

The noodles turned out to be authentic but I found out later that the Student Association sold them for forty fen a bag.

That was how I met Miao Yan for the first time, in the autumn of 1991. I was a sixteen-year-old first-year student at a university in Guangzhou, one of the most prosperous cities in south China. Of course, I didn’t know her name then.

I saw her again a month later. That evening I was having dinner with a few classmates in a restaurant on campus and our table was next to hers. Apparently half drunk, she was playing a finger-guessing drinking game with two men who could barely raise their heads from their chests. Two bottles of Wu Liang Ye and a dozen Qing Dao beers stood on the table. She lost badly in the game and as the agreed-upon punishment had to dance. While laughing aloud, she took the bottles, one by one, from the table. She stepped up on her chair and from there onto the wooden table, which shook a little under her weight. In a long-sleeved white dress, her hair pinned into a chignon at the back of her head, she looked like a goddess in the dim light.

‘What are you looking at?’ She pointed at some men at a corner table. ‘If you’ve never seen a woman before, go home and take a look at your mama.’

Her words drew loud laughter. She didn’t seem to care. She turned to the two men at her table. ‘I’m going to dance now. Be sure to get an eyeful — next time you won’t be so lucky.’

She started to spin and almost fell trying to execute a swift turn. When the restaurant owner came and attempted to pull her down from the table, she yelled at him, ‘Don’t touch my dress with your dirty paws!’ She jumped down herself, twisting her left ankle when her pink high-heeled shoes hit the floor. She took off her shoes, cursing in Cantonese, and stumbled out of the restaurant barefoot with the two men, one of whom threw a crumpled hundred-yuan bill on the floor on his way out.

Another three months passed before I finally learned this girl’s name. It was a Saturday night in spring, two months after my seventeenth birthday. We met on the rooftop of West Five, the eight-storey all-female dormitory where I lived. The rooftop was an empty expanse of white cement, half the size of a soccer field, with ventilation ducts and large pipes along the walls. It was known among the girls as a filthy place where the janitors went to fix water or heater problems, though it was quite clean. Few girls would visit it because of its emptiness and the possibility of running into rats on the way there.

I had discovered the rooftop by accident not long after I moved into the dorm. On that day, a few of my classmates and I, as delegates of the Literature Department, visited a model room on the eighth floor — the winner of that year’s university-wide competition called ‘Year’s Cleanest’. When the other students rushed into the bright room that smelled of flower-scented air freshener, I noticed a passage a few metres away at the northern corner. At the time I was looking for a quiet place to play my violin in the evenings so I ventured there after visiting the model room and thus discovered the rooftop.

I often went up there to play my violin — the open space made the sound travel further and more clearly. I played the violin in the orchestra in middle school and high school, but since coming to university, I played merely to entertain myself. It seemed a good diversion from studying. I played the same études that I had been playing for years, as well as Butterfly Lovers, a Chinese violin classic.

From the Hardcover edition.

I could have lived in the more modern Tianhe District like most of my friends but I like the narrow cobblestone alley in front of the building, where old people gather in the late afternoons under a spreading banyan tree to play mahjong or sing Cantonese opera. Across the alley is another identical apartment block. All its balconies are covered with laundry and flowers such as roses, chrysanthemums, lilies and hibiscus — Cantonese people like flowers and arrange them well, often in window boxes that decorate the streets and houses, bringing a little gentle beauty to the cityscape. Sometimes a middle-aged woman appears on a balcony, yelling in Cantonese at someone in her family to return for dinner.

I wake up every morning to the sounds of my landlord chopping meat bones in her apartment across from mine. She has lived in Guangzhou from birth. She loves to cook and has taught me how to make salt-baked chicken, beef stew clay pot and shrimp wonton noodle soup. On warm days she will prepare cold herb tea and save a cup for me. After trying many different cuisines from many different regions, I have acquired a taste for Cantonese food with its mild flavour and freshness.

On weekends I sometimes go to Shamian Island to read on the beach of the Pearl River. There, all the historical Western-style mansions are well maintained, with their white stone walls, wrought-iron banisters on the balconies shaded by banyan trees, and ornate wooden doors. The sight of them makes me think of the history in the nineteenth century when the Qing Dynasty government allowed European and American businesses to set up a trading zone here. High-rises stretch along both sides of the river. The five-star White Swan Hotel is busier than ever — now a hub for foreigners adopting Chinese orphans. I often encounter white parents on the beach, holding a Chinese baby girl they are planning to take home. Once a couple from Sweden approached me and asked if I could suggest a good Chinese name for their newly adopted baby.

After living in Guangzhou for over ten years, I have begun to fall in love with this city, not just for its amiable weather, but also for the relaxation, generosity, and down-to-earth nature of its people, which wasn’t how I felt when I first came here as a student. A decade has changed the city, and has also changed me in subtle ways that reflect my age and experience. I drawl involuntarily at the end of a sentence when speaking Mandarin — my mother tongue — as a Cantonese would; I start my Sunday mornings with dim sum and cup after cup of tea at a teahouse; I buy an orange tree for New Year and hang red envelopes on its branches to be blessed with good fortune, in accordance with the old local custom. I realise that I am becoming a citizen of my adopted city, adapting and assimilating.

I am an editor at a reference and textbook publisher. The job pays well but to me it is just a job. I go to work at eight, leave at five and never stay late. After work I often stroll to Tianhe Book City next to my office to check out the latest arrivals in the literature section. Some nights I go to a bar or coffee house with my coworkers or old college friends. We talk about work, fashion, politics, the economy, or other subjects that matter or don’t matter to us. Single again, I appreciate their companionship and enjoy spending time with them. But sometimes, when I hear them talking, my mind will stray to completely unrelated thoughts, often too random and brief to be significant — perhaps about a book, a childhood incident or a unique-looking person I just saw on the street. If I let my mind wander, I always end up thinking of Miao Yan, a college friend of mine. I have not seen her for more than ten years. Though for about eleven months we were extremely close — at least I would like to think so — I now feel I know little about her and her life.

One Saturday morning, my mother calls from my hometown, a city in another province.

‘So what do you plan to do?’ she says, after asking about the weather and the cost of living in Guangzhou.

‘I have a good job and a lot of friends.’

‘You aren’t a little girl anymore. You’re almost thirty. A woman your age should be settling down by now.’

‘Ma, I did,’ I say. ‘At least I tried.’

‘You didn’t even tell your father and me until after it happened. If you had just told us and listened —’

‘You just said I’m not a little girl anymore.’ I smile. We have had this conversation a score of times. I know she will never understand no matter how often I try to explain it.

Silence on the other end. Then, ‘A friend of your father’s called him yesterday. His son was just relocated from Beijing to Guangzhou. He’s thirty-four, also divorced. No children. He’s an engineer.’ My mother clears her throat and her voice becomes soft. ‘I think you should meet him.’

‘Don’t worry about me.’

‘I don’t understand —’

‘I’m fine. I can take care of myself. Tell Baba not to worry. Nowadays, no one cares if you’re divorced or not.’ I sit down on the bed and look at myself in the full-size mirror — sleeveless black turtleneck sweater in the latest fashion, whitish low-cut jeans with yellow seams on the sides, dark brown ponytail which is shining in the sunlight from the window, and two big silver earrings dangling above delicate but well-shaped shoulders. I am startled by how much I look like Miao Yan, except for the ponytail.

‘China isn’t America,’ my mother finally says.

‘How’s Baba?’ I ask.

Next day I spend the whole morning cleaning my apartment. Like other big cities, Guangzhou has too many cars and too few trees. If I don’t wipe my desk for two days, a thin film of dust accumulates. While organising my books, I put on the phonograph an old recording of Paganini I bought at an antique store a year ago. I used to play the violin but haven’t done so since I graduated from college. Among the books is a collection of poems from university students, a few of mine included. Even after all these years I still remember some of the poems I wrote then. They tend to have a melancholy tone, obviously written by a much younger woman.

The biggest task is tidying my wardrobe. Even if I changed my clothes twice a day for a month, it would still leave a lot unworn. I got into the habit of shopping in my senior year at university, at first purely for job interviews, but over time it became an indulgence, resulting in my overstocked walk-in wardrobe.

The white box is lying in the corner like an ice cube. It contains a black dress with straps made of shiny material, and a flower-patterned silk blouse. They used to belong to Miao Yan but are mine now. I dust the box and put it back.

In the afternoon I visit the university’s Alumni Administration Office. I am applying for graduate school in the US and need transcripts for my application. As I wait in the lobby for the documents to be signed and sealed, a woman in her early thirties joins me. She is wearing a crimson pants-suit with a pearl necklace, looking as though she has come straight from an interview. She says she needs her transcripts to get to Canada, where she is emigrating with her husband and five-year-old daughter.

‘I’ve been taking cooking classes,’ she says, shrugging like a Westerner. ‘I hear chefs make more money than librarians. Who’d hire me as a librarian in Canada anyway?’

‘Did you study library and information science?’

‘Yes, from eighty-nine to ninety-three.’

‘I was a first-year student in ninety-one,’ I say, thinking about how different the university was back then. Now it is like the centre of the city. The buses to downtown run around the clock and every week a seafood restaurant opens nearby. Students ride their bikes while talking on their cell phones.

The woman walks elegantly to a long table, pours water from a glass jug into a small paper cup, and sips it.

When she sits, I ask, ‘Do you know Miao Yan?’ My heart is pounding suddenly.

‘Sounds familiar.’

‘You were classmates.’

‘Oh, that tall girl! She’s from Sichuan, isn’t she?’

‘No. Yunnan.’

‘Maybe you’re right.’ She looks at me with curiosity. ‘How did you know her?’

‘Just coincidence. Have you seen her? Do you know where she is?’

‘Not really. We were never close. She was always on her own. I doubt she was friends with any of her other classmates.’

The administrator calls her name. She stands up, smoothing her jacket and pants. Before going inside she turns abruptly at the door. ‘Now I remember. She moved to the US a few years ago. I don’t know how she did that. Anyway, someone said she met her at a boutique store in San Francisco’s Chinatown last year. Believe it or not, she owned the store.’

I thank her and wish her good luck with the emigration.

That night I can’t sleep. The past fills me with deep emotion. I recall the evening Miao Yan and I first talked. The details return with such vividness that it seems as if I am watching a video of it — the low-hanging moon, the whitish cement ground, Miao Yan’s glittering eyes, her fluttering blouse, the way she lit her cigarette and exhaled the smoke. It is all imprinted on my memory and can never be removed.

After allowing these memories to consume me for a time I can’t measure accurately, I get up and take the white box from the closet. I put on the black dress in the bathroom — it still fits perfectly. There in the mirror, I stare at myself for the longest time. In the mirror, in my eyes, I see Miao Yan and more and more of myself at seventeen.

--

‘Noodles. Chef Kang brand. Fifty fen a bag.’

One Sunday afternoon a girl knocked on the open door of my room with a broad smile, a white cardboard box between her legs, a thick stack of money in her other hand. A few streaks of sweat anchored her splayed long hair to her rose-coloured cheeks.

‘Are you from the Student Association?’ my roommate Pingping asked, her eyes narrowed with scepticism.

‘No, but they sell Chef Kang for sixty fen a bag. You do the arithmetic.’ The girl flipped her hair behind her back and crossed her arms.

‘Who knows if your noodles really are Chef Kang?’ Donghua, another roommate of mine, poked her head out of her mosquito net — she had been knitting a sweater on her bed since noon. A week ago, she had bought a few bags of knock-off Kang noodles from a street vendor and had diarrhoea for three days.

‘I don’t carry around this box for nothing. Forget it.’ The girl bent over, picked up the box, placed it on her lifted right knee and pushed it up to her chest. The metal-tipped spikes on the high heels of her black leather shoes glittered in the sunlight.

Before she walked to the next room, I put down the book I was reading and said, ‘Give me ten bags.’

The noodles turned out to be authentic but I found out later that the Student Association sold them for forty fen a bag.

That was how I met Miao Yan for the first time, in the autumn of 1991. I was a sixteen-year-old first-year student at a university in Guangzhou, one of the most prosperous cities in south China. Of course, I didn’t know her name then.

I saw her again a month later. That evening I was having dinner with a few classmates in a restaurant on campus and our table was next to hers. Apparently half drunk, she was playing a finger-guessing drinking game with two men who could barely raise their heads from their chests. Two bottles of Wu Liang Ye and a dozen Qing Dao beers stood on the table. She lost badly in the game and as the agreed-upon punishment had to dance. While laughing aloud, she took the bottles, one by one, from the table. She stepped up on her chair and from there onto the wooden table, which shook a little under her weight. In a long-sleeved white dress, her hair pinned into a chignon at the back of her head, she looked like a goddess in the dim light.

‘What are you looking at?’ She pointed at some men at a corner table. ‘If you’ve never seen a woman before, go home and take a look at your mama.’

Her words drew loud laughter. She didn’t seem to care. She turned to the two men at her table. ‘I’m going to dance now. Be sure to get an eyeful — next time you won’t be so lucky.’

She started to spin and almost fell trying to execute a swift turn. When the restaurant owner came and attempted to pull her down from the table, she yelled at him, ‘Don’t touch my dress with your dirty paws!’ She jumped down herself, twisting her left ankle when her pink high-heeled shoes hit the floor. She took off her shoes, cursing in Cantonese, and stumbled out of the restaurant barefoot with the two men, one of whom threw a crumpled hundred-yuan bill on the floor on his way out.

Another three months passed before I finally learned this girl’s name. It was a Saturday night in spring, two months after my seventeenth birthday. We met on the rooftop of West Five, the eight-storey all-female dormitory where I lived. The rooftop was an empty expanse of white cement, half the size of a soccer field, with ventilation ducts and large pipes along the walls. It was known among the girls as a filthy place where the janitors went to fix water or heater problems, though it was quite clean. Few girls would visit it because of its emptiness and the possibility of running into rats on the way there.

I had discovered the rooftop by accident not long after I moved into the dorm. On that day, a few of my classmates and I, as delegates of the Literature Department, visited a model room on the eighth floor — the winner of that year’s university-wide competition called ‘Year’s Cleanest’. When the other students rushed into the bright room that smelled of flower-scented air freshener, I noticed a passage a few metres away at the northern corner. At the time I was looking for a quiet place to play my violin in the evenings so I ventured there after visiting the model room and thus discovered the rooftop.

I often went up there to play my violin — the open space made the sound travel further and more clearly. I played the violin in the orchestra in middle school and high school, but since coming to university, I played merely to entertain myself. It seemed a good diversion from studying. I played the same études that I had been playing for years, as well as Butterfly Lovers, a Chinese violin classic.

From the Hardcover edition.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAnchor Canada

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 0385662920

- ISBN 13 9780385662925

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages320

- Rating

US$ 4.00

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

February Flowers

Published by

Anchor Canada

(2008)

ISBN 10: 0385662920

ISBN 13: 9780385662925

Used

Softcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: Very Good. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 39971790-6

Buy Used

US$ 4.00

Convert currency

February Flowers

Published by

Anchor Canada

(2008)

ISBN 10: 0385662920

ISBN 13: 9780385662925

Used

Softcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description The book is in a very good condition. The pages do not have any notes or highlighting/underlining. Cover may show minimal signs of wear. Seller Inventory # C21A-VG-0385662920-081

Buy Used

US$ 39.89

Convert currency