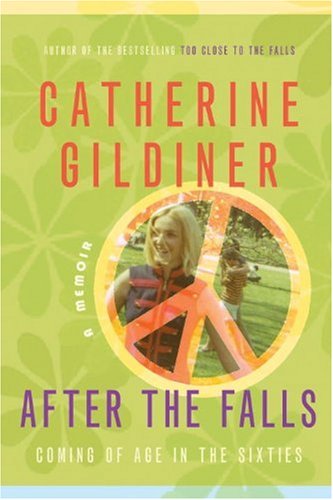

Items related to After the Falls

When Cathy McClure is thirteen years old, her parents make the bold decision to move to suburban Buffalo in hopes that it will help Cathy focus on her studies and stay out of trouble. But “normal” has never been Cathy’s forte, and leaving Niagara Falls and Catholic school behind does nothing to quell her spirited nature. As the 1960s dramatically unfold, Cathy takes on many personas — cheerleader, vandal, HoJo hostess, civil rights demonstrator — with the same gusto she exhibited as a child working split shifts in her father’s pharmacy. But when tragedy strikes, it is her role as daughter that proves to be most challenging.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

EXPULSION

As we crept up the narrow winding road that rimmed the Niagara Escarpment in our two-toned grey Plymouth Fury with its huge fins and new car smell, my father pressed the push-button gear, forcing the car to leap up the steep incline and out of our old life. The radio was playing the Ventures' hit "Walk Don't Run."

I sat in the front seat with my father while my mother sat in the back with Willie, the world's most stupid dog. We were following the orange Allied moving van, and I kept rereading the motto on the back door: leave the worrying to us. Two tall steel exhaust pipes rose in the air like minarets from both sides of the truck's cabin. Each had a flap that continually flipped open, belching black smoke and then snapping shut, like the mouth of Ollie, the dragon handpuppet on the Kukla, Fran and Ollie television show. The smoke mouths kept repeating the same phrase in unison: It's all your fault . . . it's all your fault.

I pressed my face to the window as the car crawled up the hill in first gear. Lewiston, where I'd grown up, was slowly receding. The town was nestled against the rock cliff of the huge escarpment on one side and bordered by the Niagara River on the other. St. Peter's Catholic church spire, which cast such a huge shadow when you were in the town, was barely visible from up here.

The sun was resting on the limestone cliff, setting it ablaze. I squinted at the orange embers on the rock wall, but the reflection was so glaring, I had to look away. My childhood too had gone up in flames.

~~

Yesterday I'd stood for the last time in my large bedroom with its wide-plank floor and blue toile wallpaper. My bed, which had been in my family for over 150 years, was now stripped naked, dismantled and propped against the wall. It was going to be left behind in our heritage home, no longer part of my heritage. My father said that the ceilings in our new house would not be high enough for the canopy. Where were we moving–a chicken coop?

I looked out my window at our sprawling yard and counted for the last time the thirteen old oak trees my ancestors had planted to celebrate the thirteen states in the union. The dozens of peony bushes near the wraparound porch had just opened. For generations now the church had taken flowers from our expansive gardens for the altar. I loved the part of the Mass when Father Flanagan would say, "Today's altar flowers are donated to the glory of God by the McClures."

As I loaded my new popcorn bobby socks into a box with my Lollipop underpants and turtleneck dickeys, I caught an unwelcome glimpse of myself in the mirror behind my door. I was twelve and very tall for my age, with white-blonde hair. I had no curves, not even in my calves. I resembled a Q-tip. When I'd told my mother I was hideous, she insisted that the early teenage years were an "awkward stage" and that soon I would "grow into myself"–whatever that meant.

I took a gilt-framed picture of my parents off my marble-topped dresser. It was an old photo of my father in his wool three-piece suit with his broad letterman grin, his arm casually draped around my lovely tall mother with her shy smile. It was taken years before I was born. Suddenly the words I'd overheard Delores, the cleaning lady, say to someone yesterday over the phone came back to me. She claimed it was a good thing that my mother only had one child, because two like me would have put her "in an early grave." As I glanced at the picture one more time before wrapping it in my eyelet slip, I realized how much my parents, who were in their forties when they had me, had aged. They now looked more like grandparents than parents.

~~

As the car chugged toward the top of the escarpment, I, like Lot's wife, looked back at the town below me. I had no idea then that I was leaving behind the least-troubled years of my life. Strange, since I felt there was no way I could cause more trouble than I'd caused in Lewiston.

It was 1960. We were doing what millions of other people had done: we were migrating. The Okies had left the Dust Bowl for water and we were leaving Lewiston for what my mother had mysteriously described as "opportunities." Whatever the reason, we were leaving behind the chunk of rock that was a part of us.

What would I do in Buffalo in the summer heat? When I was working at my dad' s store in Niagara Falls, I would wander over to the falls and get cooled off by the spray. I couldn't imagine not being near the rising clouds of mist that parted to reveal the perpetually optimistic rainbow.

What would my life be without the falls to ground me? Losing the falls was bad enough, but how could I leave the small, idyllic town of Lewiston, where history was around every corner? General Brock had been billeted in our house during the war of 1812. Our basement had been part of the Underground Railroad that smuggled black slaves to Canada. And would I ever again live somewhere where everyone knew me– where I knew who I was? I would no longer be the little girl who worked in her dad's drugstore. Roy, the delivery driver with whom I distributed drugs all over the Niagara Frontier, used to say if someone in Lewiston didn't know us, then they were "drifters."

~~

Soon the escarpment was only a line in the distance, and Lewiston had disappeared. I would always remember it frozen in time: the uneven bricks of Center Street under my feet; the old train track up the middle, worn down after not being used for almost a century; The Frontier House, the hotel where Dickens, James Fenimore Cooper and Lafayette stayed and the word cocktail was invented; the maple and elm trees that arched over the roads, and the Niagara River, with its swirling blue waters that snaked along the edge of town.

As we began to head south, I thought about the tightrope walker my mother and I had seen, years ago, inching across Niagara Falls carrying a long balance pole. We stood below on the lip of the escarpment, holding our breath. My mother kept her eyes shut and made me tell her what was happening.

I felt as though now, as I headed into my teenage years, it would take all I had to maintain my balance. I knew the secret was to never look down at the whirlpools below, to focus on a fixed point at eye level and keep moving. I had no idea then how much I would teeter when the winds of change in the 1960s got blowing.

My father swung the car onto a new divided highway that looked like a construction site with mounds of dirt by the side of the road The journey had become so boring that I actually started listening to my parents' conversation. Sometimes I forgot that they too were moving to a new city and a new home. I tuned in just as my father was saying, "I know it is far less money, but when I looked up the census, I found that the average salary for 1960 is only between four and five thousand dollars."

"No one earns the average salary," my mother said.

This comment worried me because my mother was always unfailingly supportive of my father. No matter what he did, she acted like it was a stroke of genius and she was delighted to be part of the arrangement. I had never before felt tension between them. Suddenly it was as though someone had vacuum-packed the car.

In an effort to regain some air, I blurted out, "Are we moving because of me?"

"No," my mother said.

My father remained silent and pressed in the lighter to reignite his El Producto cigar, which was starting to make me carsick. He looked in the rearview mirror at my mother, sending her a glance with an arched eyebrow. Clearly he disagreed with her.

She said, "Well, it is true that we think you would be happier in a larger place. The world seems to be aching to change a bit . . . and Lewiston is having growing pains."

"Change? What needs to change?" I asked.

"I don't mean change exactly; I just think we all need a broader scope," she said. "Different kinds of people– looking out at the world instead of closing the world out."

My father was still looking in the rear-view mirror, and although he barely moved a muscle, I could tell he was shocked that my mother was saying such things. He had no idea what in my mother' s world could possibly need broadening.

When my father had announced the move, he said we were going for "new business prospects." He said that the economy had changed and that pretty soon there wouldn't be any more small, family-run drugstores. I had never thought our drugstore was small– I thought of it as enormous. He maintained that the world was being taken over by "chain stores." I didn't know what these were; I thought at first that he meant hardware stores that sold shackles. He explained how chain stores worked out better prices from the drug companies, how they didn' t make specialty unguents and didn't deliver. Most of the work was done by pharmacy assistants. He could no longer compete; it was time to get out before we were forced out.

Did he really think these chain-type-stores would catch on? Had he forgotten about loyalty? I thought of all the times Roy and I had risked our lives delivering medication on roads with blowing snow and black ice, or worked after midnight to get someone insulin. It was my father who always said that customers would appreciate the service and be loyal. But just days ago, when I'd questioned him on this, he said that people could be fickle and that their loyalty was to the almighty dollar. All the service in the world couldn't keep a customer if Aspirin is cheaper elsewhere.

When I said that was terribly unfair, he pointed out that that was just human nature. People did what was best for themselves at any given time. I'd never heard him speak so harshly. He'd usually espoused kindness and "going the extra mile." He put his arm around me and said that the world was changing and it was best to move on. You couldn't stop progress. After all, America hailed the Model T; no one cried for the blacksmith.

As we drove along the ugly, detour highway, weaving between gigantic rust-coloured generators that obscured the view of the rock cliffs and the river, I asked why, since we must be getting near the city of Niagara Falls, we didn't see the silver mist of the falls spraying in the air like a geyser. My father told me the highway we were on was being built by Robert Moses (who would coincidentally name it the Robert Moses Parkway, though I never saw a park). Moses designed it so that tourists would be diverted from the downtown core of Niagara Falls and forced to drive by his monument of progress, the Niagara Power Project. No one would drive through the heart of Niagara Falls any more, which is where our drugstore was. My father predicted, accurately as it turned out, that the downtown would soon die.

~~

After about a half-hour, my father circled off the New York State Thruway onto a futuristic round basket-weave exit marked Amherst. "Wait until you see how convenient this home is for getting on the highway and travelling," he said.

I wondered where we would be going since my father said travelling spread disease.

A minute later he swung into a suburban housing development with a sign that read kingsgate village, and then onto Pearce Drive. When he turned into a driveway, I was too taken aback to say anything. In front of us was a tiny green clapboard bungalow with pink trim. All around it were identical houses with slightly different frontispieces. My father had picked out this place, but I felt his mortification at having to show it to us. It started to sink in that our historical colonial home with the huge wraparound porch was now history.

Why my mother had not been included in the house hunt was a mystery to me. It wasn't like she was busy. She'd never in my memory cooked, cleaned or held a job.

She was trying to find nice things to say. "Well, this should be easy to look after. No big yard to rake."

But I could feel her slowly withering, cell by disappointed cell.

A man in the next yard, which was hard to distinguish from our toupée of green turf, was outside cutting the lawn in his tank-style undershirt. Suspenders held up his pants, forming a kind of empire waistline directly under his surprisingly large breasts. He waved and said, "Howdy."

"Who is that– Humpty Dumpty?" I asked.

My mother shot me a look that said it was best not to make fun of anyone who would be our neighbour in what was to be our neighbourhood.

We got out of the car and I stood in the driveway, peering inside through the kitchen window. The floor had linoleum with a design of faux pebbles, the kind that would surround the moat if you lived next door to Sir Lancelot. The walls were covered in fake brick contact paper with fake ivy growing up it.

The moving van pulled up. As one mover chomped on a hoagie, the other jumped down from the cab, looked at the house and said to my father, "There's no way you are ever going to fit these huge pieces of furniture into this place. What am I supposed to do with them?" The front door was obviously too narrow for the French armoires and early American dressers.

My father said nothing. I had never seen him look as though he was not in charge. He just went and sat on the porch, which was actually a cement stoop. My mother, who'd inherited these antiques and cherished them, ordered the movers to unload everything onto the driveway. Then she said to my father, "Not to worry, Jim. Some of these things have been in my family for far too long. It's progress–we'll clear out some of it– deadwood."

I braced myself and followed my parents inside. My room was tiny, and now I knew why my father had said I couldn't bring my canopy bed. A single bed could barely fit in this cubbyhole. It was the size of my walk-in closet in Lewiston. Cheap cotton curtains printed with faded red Chinese pagodas adorned two small sliding aluminum windows that were too high to see out of. Since there was nothing else to look at, I went back to the living room, where my mother stood looking lost while my father was in the bathroom. Even with the door closed we heard everything, as though we were standing next to him. I just stared at the floor and so did my mother.

During the move the men broke a silver and marble ashtray, the kind that stood by an easy chair and opened like a yawn to swallow still-smouldering butts. My father said, "You'll pay for that. I' m making out a report on it right now and I'll be sure to mention your lack of care." It was unlike my father to get rattled and speak to people in an impolite tone.

Later, in the driveway, I overheard one mover, who wore his disdain in his every gesture, say to his partner, "The guy's worried about his precious ashtray?"

The other said, "He told me this place is just a stopover till his new split-level is finished."

The movers exchanged glances.

Once the weensy rooms were filled, my father, bewildered, stared at the ocean of antiques in the driveway. He said to my mother, "When I saw this place it was empty. I don't remember it being so small."

My mother refused to watch as the movers hoisted the furniture into the attic of the garage. Marble tabletops were removed with crowbars and stored in pieces. Most of the pieces would eventually warp from freezing temperatures and moisture. My parents would never sell them or look at them again.

~~

My mother had inherited a large collection of historical lithographs of Niagara Falls that she had enhanced with her own acquisitions. She had spent much of my childhood going to auctions and purchasing lithographs from all over the world. In one antique lithograph journal her colle...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherKnopf Canada

- Publication date2009

- ISBN 10 0307398226

- ISBN 13 9780307398222

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

After the Falls

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0307398226

After the Falls

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 1.1. Seller Inventory # 0307398226-2-1

After the Falls

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 1.1. Seller Inventory # 353-0307398226-new

After the Falls

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0307398226

After the Falls

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0307398226

After the Falls

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0307398226