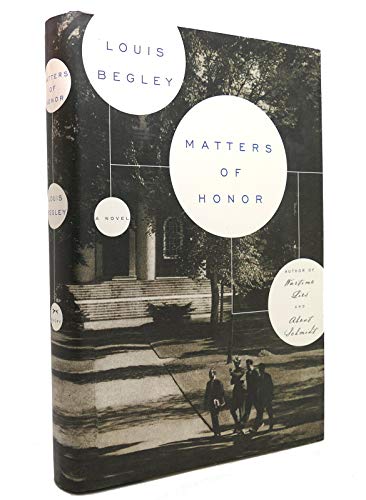

Items related to Matters of Honor

From the acclaimed author of Wartime Lies and About Schmidt, a luminous story of a brilliant but haunted outsider driven to transcend his past.

At Harvard in the early 1950s, three seemingly mismatched freshmen are thrown together: Sam, who fears that his fine New England name has been tarnished by his father’s drinking and his mother’s affairs; Archie, an affable army brat whose veneer of sophistication was acquired at an obscure Scottish boarding school; and Henry, fiercely intelligent but obstinate and unpolished, a refugee from Poland via a Brooklyn high school. As roommates they enter a world governed by arcane rules, where merit is everything except when trumped by pedigree and the inherited prerogatives of belonging. Each roommate’s accommodation to this world will require self-reinvention, none more audacious than Henry’s. Believing himself to be at last in the “land of the free,” he is determined to see himself on a level playing field, playing a game he can win. The ante is high—virtual renunciation of his past—but the jackpot seems even higher—long dreamed-of esteem, success, and arrival. Henry will stay in the game almost to the last hand, even after it becomes clear he must stake his loyalty to his parents and even to himself.

Reserved and observant, Sam recounts the trio’s Harvard years and the reckonings that follow: his own struggle with familial demons and his rise as a novelist; a coarsened Archie’s descent into drink; and, most attentively, Henry’s Faustian bargain and then his mysterious disappearance just as all his wildest ambitions seem to have been realized. Love and loyalty will impel Sam to discover the secret of Henry’s final reinvention.

An unforgettable portrait of friendship and a meditation on loyalty and honor—Louis Begley’s finest achievement.

At Harvard in the early 1950s, three seemingly mismatched freshmen are thrown together: Sam, who fears that his fine New England name has been tarnished by his father’s drinking and his mother’s affairs; Archie, an affable army brat whose veneer of sophistication was acquired at an obscure Scottish boarding school; and Henry, fiercely intelligent but obstinate and unpolished, a refugee from Poland via a Brooklyn high school. As roommates they enter a world governed by arcane rules, where merit is everything except when trumped by pedigree and the inherited prerogatives of belonging. Each roommate’s accommodation to this world will require self-reinvention, none more audacious than Henry’s. Believing himself to be at last in the “land of the free,” he is determined to see himself on a level playing field, playing a game he can win. The ante is high—virtual renunciation of his past—but the jackpot seems even higher—long dreamed-of esteem, success, and arrival. Henry will stay in the game almost to the last hand, even after it becomes clear he must stake his loyalty to his parents and even to himself.

Reserved and observant, Sam recounts the trio’s Harvard years and the reckonings that follow: his own struggle with familial demons and his rise as a novelist; a coarsened Archie’s descent into drink; and, most attentively, Henry’s Faustian bargain and then his mysterious disappearance just as all his wildest ambitions seem to have been realized. Love and loyalty will impel Sam to discover the secret of Henry’s final reinvention.

An unforgettable portrait of friendship and a meditation on loyalty and honor—Louis Begley’s finest achievement.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Louis Begley lives in New York City. His previous novels are Wartime Lies, The Man Who Was Late, As Max Saw It, About Schimdt, Mistler’s Exit, Schmidt Delivered, and Shipwreck.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Chapter 1

This is my first memory of Henry: I stand at the door of one of the three bedrooms of the ground floor suite in the college dormitory to which I have been assigned. At the open window, with his back to me, a tall, slender, red-haired boy is leaning out and waving to someone. He has heard my footsteps, turns, and beckons to me saying, Take a look, a beautiful girl is blowing kisses to me. I've never seen her before. She must be mad.

I went to the window. Not more than ten feet away, a girl standing on the grass was indeed blowing kisses and waving her hand in the direction of our window. Between kisses, she grinned, her mouth made to seem very large by a thick layer of red lipstick. She wore a suit of beige tweed, dark green stockings, and a Tyrolean hat with a little pheasant feather. A couple of paces away from her I saw a middle-aged woman, in darker tweeds and a brown fedora. Something about her—the hat? an air of haughty distinction?—made me think of Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca, about to board the plane for Lisbon. I assumed, partly on account of their similar dress, that she was the girl's mother.

Several undergraduates had stopped on the path leading diagonally to the far corner of the Widener and were gawking at the scene. Neither the daughter's antics nor the audience they had attracted seemed to disturb the mother. But after a few more minutes she said something in a voice too low for us to hear, and the girl, having blown one more kiss, threw up her arms in theatrical despair. They strolled away.

I'm in love, sighed the red-haired boy. I want to throw myself at her feet.

Why don't you? I replied, only half kidding. It's not too late. Climb out the window right now and you won't even have to run to catch them.

Oh no, he wailed, I can't. Why did this have to happen today, when I'm not prepared?

As there wasn't a trace of irony in his voice or expression, I should have let the subject drop. Instead, I told him that, while a formal declaration might be premature, no harm could come of his proposing a cup of coffee in the Square.

He shook his head bitterly. I don't dare, he said. Don't you see how splendid she is? Penthesilea in tweeds! None but the son of Peleus could tame her. I am unworthy even of her scorn.

His face was a mask of discouragement.

I suppose that I shrugged. That or perhaps the expression on my face must have told him that I thought he had gone overboard. He recomposed his face into a bland smile and said, I suppose you are one of my roommates. I'm Henry White . . . from New York.

I had met New Yorkers before, mainly at school, although a number of New York families had summerhouses in the vicinity of Lenox, where my parents and I lived, and in the neighboring Berkshire towns of Stockbridge, Great Barrington, and Tyringham. This fellow didn't sound like any of them. He didn't mispronounce. In fact his speech was oddly slow and accurate, except when he got excited, as during the Peleus routine, with a thickness around the edge of words suggesting a dry mouth. It occurred to me that he might be some kind of foreigner, but, if he had an accent, I couldn't identify it. My notions of how foreigners spoke derived at the time exclusively from the movies and the French family with whom I had just spent the summer in a small town north of Paris. That Henry White of New York didn't have a French accent was quite clear.

I confirmed that I was indeed his roommate and, having introduced myself as Sam Standish, examined Henry more closely. His clothes were wrong; they looked brand-new. The jacket and trousers were of an odd color. Other than that, he was a fine-looking fellow. Is Sam short for Samuel? he asked me earnestly. He nodded when I confirmed that this was the case.

I hadn't had lunch and asked whether he would like to have a sandwich with me in the Square. He said that he had already eaten at the Freshman Union. I went out alone.

Courses weren't going to start for another couple of days, but the dormitories were open, and freshman orientation was in progress. I had assured my mother that I could get down to Cambridge by bus, even with my big footlocker. To my surprise, she had insisted that she really wanted to drive me down. But since she and my father were going out to dinner that evening, she wouldn't have lunch with me. She gave me a couple of bills, the cost of lunch for two by her reckoning, and sped off as soon as I had unpacked the car trunk. I had dragged my stuff into the living room of the suite and saw that I wasn't the first to arrive. Someone's luggage was in the middle of the room. Then I stuck my head into one of the bedrooms and came upon Henry.

After a solitary tuna-salad sandwich at Hayes-Bickford, I returned to the dormitory. Henry may have been watching for me at the window. In any event, he opened the door of the suite before I could turn the key in the lock and said he was glad I had come back so soon. He had a practical question he wanted to ask: Did I care which bedroom he took? He had spent the previous night in the one I had found him in but didn't think that gave him any sort of prior claim. He asked me to follow him to the bedroom he wanted and pointed to the right toward a dark brick classroom building shaped like a whale.

That's Sever, he said, an H. H. Richardson design, and over here, right in front of us, is Memorial Church.

I said that he could keep the room. The three bedrooms were all the same size, and I didn't care about the view. That Sever was a masterpiece of late-nineteenth-century American architecture was unknown to me then, but I don't think that knowing it would have made any difference. I didn't expect to spend much time at the window. Henry, very pleased, sat on my desk chair while I unpacked. When I finished, he helped me make the bed.

The ice had been broken, it seemed, so I asked why he hadn't at least spoken to the girl. After all, she was blatantly trying to pick him up. Henry shook his head and said it was out of the question. The timing was fatally wrong. He might have followed her to find out whether she went to Radcliffe, and in which dorm she lived, but his conspicuous red hair ruled that out. People recognized him instantly. If the girl or her mother had turned around and seen him, they'd know it was he and would think he was some kind of nut who couldn't understand a joke. That would have spoiled everything. He would have to wait.

You're nuts, I told him. There is no possible harm in her and her mother's knowing that you'd like to shake the hand of the girl who took the trouble to blow kisses at you.

He shook his head again. Timing, he said, timing. The stars aren't aligned. I have to wait.

It was none of my business, and probably I should have known enough not to insist on a subject that made him uneasy. But as I was condemned to room with Henry for a year, I thought I was entitled to investigate whether he was a pompous jerk or really deranged.

These questions did not preoccupy me long. Within a couple of weeks, Henry decided that we were close friends—a conclusion I had not yet reached—and he began to unburden himself to me about his feelings with such unsparing frankness and volubility that I sometimes found myself wishing I hadn't done whatever had put him so at ease. Unprompted by me, he spoke again about the girl and acknowledged his behavior as peculiar. It wasn't shyness, he insisted, that had stopped him in his tracks, but a conviction that he must make himself suitable first or face inevitable rejection—not only by this girl and her mother but by every other girl he might find attractive.

And it's not just girls, he said, I mean rejected by everyone here! Do you remember the Raymond Massey character in Arsenic and Old Lace, the one whom Dr. Einstein, the Peter Lorre character, made into a monster by botching the operation on his face? Raymond Massey is me. I too have been botched. And therefore I say: Dr. Einstein, we must operate again!

I said this was more evidence that he was nuts.

He shook his head and said that observations he had made during just two meals, dinner and lunch, that he had eaten alone at the Union, before I arrived to find him standing at the window, had confirmed his fears. He was hopelessly out of place in this world of creatures like the girl or me for that matter. He had watched the freshmen milling about the place, studied their appearance and manner, and saw no one like him. Certainly no one dressed like him. Or, put another way, no one he would have wanted to know who looked anything like him or had equally disastrous clothes.

While recounting these experiences, he laughed so hard he had tears in his eyes. I didn't know what to make of this and suggested that his survey of the freshman class might not be scientific. Henry said that could be. But as I would come to see, in fact Henry missed little of what went on and, as a rule, remembered everything. For now he granted my point and reduced his claim: the Freshman Union survey had confirmed what he had already realized at home, before leaving for Cambridge, when his mother was packing the things he was to take with him to college. I was by then familiar with them: a sky-blue suit he had worn at his high school graduation, a tan flannel jacket, and two pairs of brown trousers. His mother had chosen every item, and every item was too large because she expected him to grow into it and seemed unwilling to admit that he had reached his full height. He had begged to be allowed to buy his clothes in Cambridge or Boston once he knew how other people dressed, but she wouldn't hear of it: he was too irresponsible and extravagant, and he had no appreciation of quality. Besides, he said, the way she looks at it, it's my father's money and she is entitled to the fun of spending it. That's how she has gotten me to look like an underage bookkeeper.

By that time, I had gotten used to Henry's wardrobe, but when I recalled our first meeting, and the im...

This is my first memory of Henry: I stand at the door of one of the three bedrooms of the ground floor suite in the college dormitory to which I have been assigned. At the open window, with his back to me, a tall, slender, red-haired boy is leaning out and waving to someone. He has heard my footsteps, turns, and beckons to me saying, Take a look, a beautiful girl is blowing kisses to me. I've never seen her before. She must be mad.

I went to the window. Not more than ten feet away, a girl standing on the grass was indeed blowing kisses and waving her hand in the direction of our window. Between kisses, she grinned, her mouth made to seem very large by a thick layer of red lipstick. She wore a suit of beige tweed, dark green stockings, and a Tyrolean hat with a little pheasant feather. A couple of paces away from her I saw a middle-aged woman, in darker tweeds and a brown fedora. Something about her—the hat? an air of haughty distinction?—made me think of Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca, about to board the plane for Lisbon. I assumed, partly on account of their similar dress, that she was the girl's mother.

Several undergraduates had stopped on the path leading diagonally to the far corner of the Widener and were gawking at the scene. Neither the daughter's antics nor the audience they had attracted seemed to disturb the mother. But after a few more minutes she said something in a voice too low for us to hear, and the girl, having blown one more kiss, threw up her arms in theatrical despair. They strolled away.

I'm in love, sighed the red-haired boy. I want to throw myself at her feet.

Why don't you? I replied, only half kidding. It's not too late. Climb out the window right now and you won't even have to run to catch them.

Oh no, he wailed, I can't. Why did this have to happen today, when I'm not prepared?

As there wasn't a trace of irony in his voice or expression, I should have let the subject drop. Instead, I told him that, while a formal declaration might be premature, no harm could come of his proposing a cup of coffee in the Square.

He shook his head bitterly. I don't dare, he said. Don't you see how splendid she is? Penthesilea in tweeds! None but the son of Peleus could tame her. I am unworthy even of her scorn.

His face was a mask of discouragement.

I suppose that I shrugged. That or perhaps the expression on my face must have told him that I thought he had gone overboard. He recomposed his face into a bland smile and said, I suppose you are one of my roommates. I'm Henry White . . . from New York.

I had met New Yorkers before, mainly at school, although a number of New York families had summerhouses in the vicinity of Lenox, where my parents and I lived, and in the neighboring Berkshire towns of Stockbridge, Great Barrington, and Tyringham. This fellow didn't sound like any of them. He didn't mispronounce. In fact his speech was oddly slow and accurate, except when he got excited, as during the Peleus routine, with a thickness around the edge of words suggesting a dry mouth. It occurred to me that he might be some kind of foreigner, but, if he had an accent, I couldn't identify it. My notions of how foreigners spoke derived at the time exclusively from the movies and the French family with whom I had just spent the summer in a small town north of Paris. That Henry White of New York didn't have a French accent was quite clear.

I confirmed that I was indeed his roommate and, having introduced myself as Sam Standish, examined Henry more closely. His clothes were wrong; they looked brand-new. The jacket and trousers were of an odd color. Other than that, he was a fine-looking fellow. Is Sam short for Samuel? he asked me earnestly. He nodded when I confirmed that this was the case.

I hadn't had lunch and asked whether he would like to have a sandwich with me in the Square. He said that he had already eaten at the Freshman Union. I went out alone.

Courses weren't going to start for another couple of days, but the dormitories were open, and freshman orientation was in progress. I had assured my mother that I could get down to Cambridge by bus, even with my big footlocker. To my surprise, she had insisted that she really wanted to drive me down. But since she and my father were going out to dinner that evening, she wouldn't have lunch with me. She gave me a couple of bills, the cost of lunch for two by her reckoning, and sped off as soon as I had unpacked the car trunk. I had dragged my stuff into the living room of the suite and saw that I wasn't the first to arrive. Someone's luggage was in the middle of the room. Then I stuck my head into one of the bedrooms and came upon Henry.

After a solitary tuna-salad sandwich at Hayes-Bickford, I returned to the dormitory. Henry may have been watching for me at the window. In any event, he opened the door of the suite before I could turn the key in the lock and said he was glad I had come back so soon. He had a practical question he wanted to ask: Did I care which bedroom he took? He had spent the previous night in the one I had found him in but didn't think that gave him any sort of prior claim. He asked me to follow him to the bedroom he wanted and pointed to the right toward a dark brick classroom building shaped like a whale.

That's Sever, he said, an H. H. Richardson design, and over here, right in front of us, is Memorial Church.

I said that he could keep the room. The three bedrooms were all the same size, and I didn't care about the view. That Sever was a masterpiece of late-nineteenth-century American architecture was unknown to me then, but I don't think that knowing it would have made any difference. I didn't expect to spend much time at the window. Henry, very pleased, sat on my desk chair while I unpacked. When I finished, he helped me make the bed.

The ice had been broken, it seemed, so I asked why he hadn't at least spoken to the girl. After all, she was blatantly trying to pick him up. Henry shook his head and said it was out of the question. The timing was fatally wrong. He might have followed her to find out whether she went to Radcliffe, and in which dorm she lived, but his conspicuous red hair ruled that out. People recognized him instantly. If the girl or her mother had turned around and seen him, they'd know it was he and would think he was some kind of nut who couldn't understand a joke. That would have spoiled everything. He would have to wait.

You're nuts, I told him. There is no possible harm in her and her mother's knowing that you'd like to shake the hand of the girl who took the trouble to blow kisses at you.

He shook his head again. Timing, he said, timing. The stars aren't aligned. I have to wait.

It was none of my business, and probably I should have known enough not to insist on a subject that made him uneasy. But as I was condemned to room with Henry for a year, I thought I was entitled to investigate whether he was a pompous jerk or really deranged.

These questions did not preoccupy me long. Within a couple of weeks, Henry decided that we were close friends—a conclusion I had not yet reached—and he began to unburden himself to me about his feelings with such unsparing frankness and volubility that I sometimes found myself wishing I hadn't done whatever had put him so at ease. Unprompted by me, he spoke again about the girl and acknowledged his behavior as peculiar. It wasn't shyness, he insisted, that had stopped him in his tracks, but a conviction that he must make himself suitable first or face inevitable rejection—not only by this girl and her mother but by every other girl he might find attractive.

And it's not just girls, he said, I mean rejected by everyone here! Do you remember the Raymond Massey character in Arsenic and Old Lace, the one whom Dr. Einstein, the Peter Lorre character, made into a monster by botching the operation on his face? Raymond Massey is me. I too have been botched. And therefore I say: Dr. Einstein, we must operate again!

I said this was more evidence that he was nuts.

He shook his head and said that observations he had made during just two meals, dinner and lunch, that he had eaten alone at the Union, before I arrived to find him standing at the window, had confirmed his fears. He was hopelessly out of place in this world of creatures like the girl or me for that matter. He had watched the freshmen milling about the place, studied their appearance and manner, and saw no one like him. Certainly no one dressed like him. Or, put another way, no one he would have wanted to know who looked anything like him or had equally disastrous clothes.

While recounting these experiences, he laughed so hard he had tears in his eyes. I didn't know what to make of this and suggested that his survey of the freshman class might not be scientific. Henry said that could be. But as I would come to see, in fact Henry missed little of what went on and, as a rule, remembered everything. For now he granted my point and reduced his claim: the Freshman Union survey had confirmed what he had already realized at home, before leaving for Cambridge, when his mother was packing the things he was to take with him to college. I was by then familiar with them: a sky-blue suit he had worn at his high school graduation, a tan flannel jacket, and two pairs of brown trousers. His mother had chosen every item, and every item was too large because she expected him to grow into it and seemed unwilling to admit that he had reached his full height. He had begged to be allowed to buy his clothes in Cambridge or Boston once he knew how other people dressed, but she wouldn't hear of it: he was too irresponsible and extravagant, and he had no appreciation of quality. Besides, he said, the way she looks at it, it's my father's money and she is entitled to the fun of spending it. That's how she has gotten me to look like an underage bookkeeper.

By that time, I had gotten used to Henry's wardrobe, but when I recalled our first meeting, and the im...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherKnopf

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 0307265250

- ISBN 13 9780307265258

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages320

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 42.41

Shipping:

US$ 12.74

From United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Matters of Honor

Published by

Alfred a Knopf Inc

(2007)

ISBN 10: 0307265250

ISBN 13: 9780307265258

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 320 pages. 9.50x6.75x1.50 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0307265250

Buy New

US$ 42.41

Convert currency

Matters of Honor

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks74783

Buy New

US$ 59.00

Convert currency

MATTERS OF HONOR

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.35. Seller Inventory # Q-0307265250

Buy New

US$ 75.00

Convert currency